Fielding Physical Intelligence

We expect tech to improve outcomes; under what conditions?

The question isn’t whether the technology works.

It usually does. The sensors detect. The models predict. The dashboards display. Pilots pass. Demos impress.

The question is whether the system — the full stack of tools, workflows, people, and pressures — produces an outcome anyone would call favorable. Not in a controlled environment. On a job site running behind. On a farm where the margin doesn’t forgive experimentation. In the hands of someone responsible for fifteen things who has to decide, in the moment, whether this is worth the friction.

That’s a systems question. And systems don’t fail in demos. They fail under load.

Construction

In Sydney’s construction sector, sites log roughly thirty-five serious injury claims every workday. Each one a person who went to work and didn’t come home the same.

Safe Work Australia estimates workplace injuries cost the New South Wales’ economy $28.6 billion annually — the equivalent of an entire metro line, gone. Money gone to compensate workers and grieving families.

Tools everywhere

Compliance platforms. Documentation systems. Digital checklists.

Technically adequate. Often ignored.

Not because crews don’t care.

Because a foreman stretched across fifteen problems, on a site three days behind, under cost pressure, doesn’t have the cognitive bandwidth for a system that adds steps. The paperwork gets filed. The hazard doesn’t get seen.

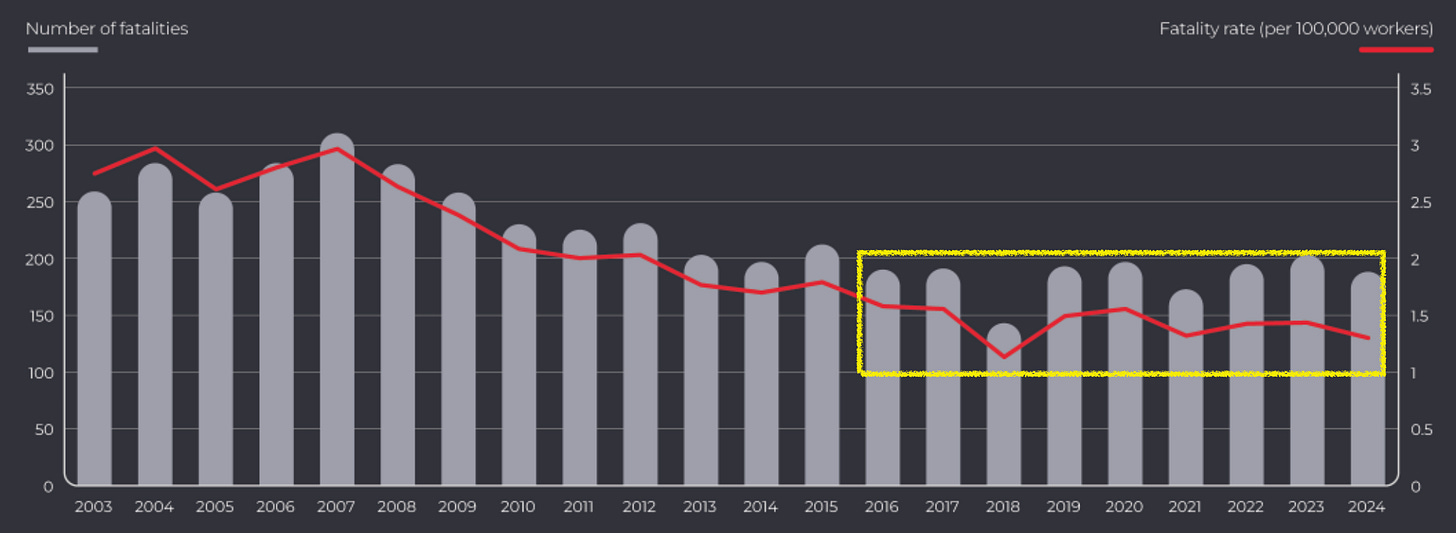

As a result, safety standards plateau. The nationwide fatality rates tells the story:

Nine years. The line hasn’t moved.

This isn’t a tool failure. It’s a system failure. The tools were never the constraint. The constraint is the conditions under which someone has to use them.

Agriculture

Model meet Reality

John Deere is a $130B company. Its See & Spray system — trained to identify weeds in early-season fields — required retraining after failing mid-summer in the same US farms. The crops had grown. The model hadn’t accounted for it.

Fahad Khan, head of product management for Blue River, John Deere’s platform handling data put it plainly:

“Sometimes it’s impossible to identify a weed from a crop,” Khan said. “If you ask my 50-plus ML engineers, they wouldn’t know.”

At a recent agtech conference, Nida Mahmoed asked the question that silenced the room: “Are farmers actually making more money?” Speaker after speaker had celebrated efficiency gains — water savings, yield improvements, smart pest detection.

But yield isn’t income.

A farmer with 35% more output who gets undercut at the market gate is still struggling.

We keep building for performance metrics.

Metrics that matter

The numbers that get celebrated in pitch decks — accuracy, efficiency, adoption in pilots — aren’t the numbers operators live by.

Even the most capital-rich technology category is hitting this wall: MIT reported that 95% of generative AI pilots failed to reach production in the first half of 2025.

Not because the models didn’t perform.

Because nobody had (fully) designed what satisfies the end user.

Context as architecture

The assumption underneath most deployment is that knowledge generalizes. That a model trained in Iowa transfers to Pakistan. It doesn’t.

That a workflow designed in an office will succeed, let alone be adopted on a construction site. It rarely does.

Physical systems operate under constraints that don’t appear in demos.

Weather.

Regulation.

Labor availability.

Generational knowledge that doesn’t fit in a dataset.

Time pressure that makes “optimal” irrelevant.

The technology that survives isn’t the most sophisticated. It’s the technology built for how work actually happens — compressing decisions rather than adding steps, fitting existing rhythms before asking anyone to change.

Operational excellence isn’t a feature.

It’s a design constraint.

This is what I’ll be exploring: conversations with operators building and deploying technology in physical systems — agriculture, construction, infrastructure. The patterns that separate tools that ship from tools that stick.

Not success stories. Observations from the field.

First up: precision agronomy in Australia.